Timeless Tethers

“Portrait of King George III” by Thomas Gainsborough, circa 1781

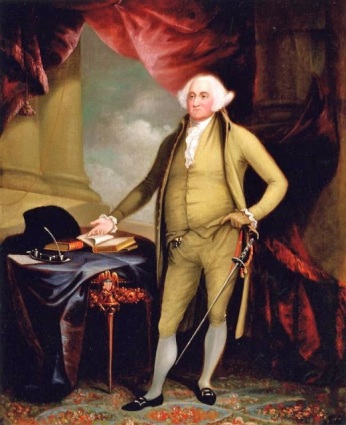

I love this portrait of King George. He has such a poor reputation, but if you had undiagnosed porphyria in an era when bleeding was supposed to cure all ills, you’d have a pretty rough time, too. Anyway, I love this portrait of him. In fact, it’s one of my favorite 18th century male portraits because he’s so simply dressed, but he’s wearing every piece of a true gentleman’s wardrobe, including the elusive fashion garter, pinky ring, and watch chain!

Though the watch emerged as the premier toy of the nobility in the 16th and 17th century, in the 18th century, watches became an indispensable accessory. Not only were they tiny marvels and works of art, they also denoted fashionable scientific enlightenment– the transition from the ancient sundial to the mathematical precision of a rapidly industrializing society. Early watches were heavily ornate and often only had an hour hand. Thanks in large part to advances in enameling techniques, by the 18th century, decoration became more refined: smooth enamel scenes and repoussé cases contrasted beautifully with clean, white watch faces. Minute and second hands were introduced and complex calendar watches with multiple faces became popular.

Double-faced Calendar Watch with Enamel Painting, circa 1770-80

Early watches often only had an hour hand. By the 18th century, minute hands had become standard and second hands began to show up on fancier models.

Watch with Pearls (front and back), circa 1790-1800

18th century gentlemen wore watch chains attached their timepieces because they helped make it easy to check the time without having to root inelegantly in a tiny pocket. Watch chains were long enough to show from under the waistcoat:

Watch Chain, circa 1800

“Portrait of John Adams” by William Winstanley, circa 1798

Today, we call these kinds of chains fobs. However, the word “fob” originally referred not to the chain itself, but to the small pocket in which valuables, like a watch, were kept. Breeches in the 18th and early 19th century had wide waistbands with small pockets fitted into them, a tradition continued by many modern pairs of jeans:

The etymology for the word: fob (n.) 1653, “small pocket for valuables,” probably related to Low Ger. fobke “pocket,” High Ger. fuppe “pocket.”

Suit, circa 1765-75

If you look closely at the waistband of the breeches, you will see the welt of the fob/pocket opening (you may have to expand the picture). This suit is missing its waistcoat, which would cover the waistband and conceal the pocket. It’s easy to slip a watch into a tiny pocket, but getting it out can be much harder! A watch could be tucked into this pocket and the attached chain would hang out of the pocket making it easy to remove.

Trousers with fob (pocket), circa 1810-20

The waistcoats of the 19th century were much shorter, so accessing the fob pocket was much less difficult. The watch chains of the era were much shorter, though the Merveilleuses kept the tradition of displaying lots of small watch charms popular. By the Victorian era, watch chains had become much simpler and remained so throughout the era.

Modern pair of jeans with a small fob pocket inside the larger front pocket.

So in the 18th century, the fob was the pocket and the watch chain was what you attached your watch to. However, many museums, especially American museums, label them (and even some equipages/chatelaines) as fobs. The confusion may stem from the fact that many earlier 18th century men’s watch chains are not chains at all, but watch strings made of ribbons, tassels and other passementerie:

Fob Design, circa 1780

Watch strings were more common than chains because they were less expensive and hardier.

Silk Watch Chain with Seal, circa 1770-90

Woven Hair Watch Chain with Watch Key, circa 1780-1800

Braided Silk Watch Chain with Watch Key, circa 1770-1790

The image is terrible quality, but I love the fly fringe. Fly fringe for all!

Watch chains held more than just the watch. Dangling from the ends, you’ll notice small trinkets. This little “charms” were actually necessary to conducting 18th century business and no gentleman of means would be caught without them. The two most common men’s accessories were the watch key and seal.

Watch Chain with Seal and Key, circa 1800

Citrine Seal, circa 1815

The seal was used for sealing letters. In an age where paper correspondence was the only means of long-distance communication, letters were part of everyday life. Our current mail system is very sterilized compared to mail systems of the past. Letters were not handled by machines, but by people, some of whom might take an interest in what your private letter contained. A wax seal provided both proof of the sender (to avoid forgeries), but also added a tamper-evident seal. It wasn’t a perfect system, but adding seals to documents was an important part of law and etiquette.

Watch and Key, circa 1770, via the Met Museum

Watches often became separated from their keys over the years. Fortunately, unlike house keys, watch keys were fairly standardized, so you could buy another from a watch maker.

Thomas Jefferson’s Watch Key honoring his late wife, Martha

Since pocket watches run on springs, it was important to keep your watch carefully wound in order for it to continue keeping time. Stem-wind pocket watches (the ones still in use today) were not invented until the 1840s. Instead, watches were wound with small watch keys. You’ll notice many pre-1850 watches have small holes in the face with a pin inside. This is where the watch key would be inserted to wind the watch. Pocket watches must be wound daily to keep functioning properly, so it makes sense to keep your key close at hand on your watch chain, just in case you notice your watch running down!

Aside from his watch and these small business implements, perhaps a few tassels for good fun, a man’s watch chain might include small trinkets, like a portrait miniature or a charm for military service. Women, however, often carried much more than these basic accessories on shorter, heavily decorated pieces of jewelry called an equipage (later called a chatelaine). Women did not wear breeches with fob pockets, so while men hid their watches in a fob pocket and let the watch chain hang from it, women wore their watches at the hanging end of their equipages in full view:

“Ulrike Sophie, Duchess of Mecklenburg,” circa 1765

There are multiple versions of this portrait and this dress (it must have been a favorite of hers). If you look under her elbow, you can see she is wearing a lovely watch and equipage.

Chatelaine with Watch, circa 1760

The word “chatelaine” is, like “fob,” a 19th century term. Most museums will list equipages as chatelaines in their collections.

Back of the chatelaine showing the hook

Equipages pinned or clipped to the waistband of a woman’s petticoat since she didn’t have a fob pocket. Others were designed to be worn hooked over a sash, like those worn over zone-front gowns. The weren’t just for watches, but could also include a multitude of accessories, grooming tools, sewing implements, or small vials of perfume and did not necessarily have to include a watch–some were more like suspended sewing kits–but for the sake of brevity, I’m going to focus only on chatelaines with watches:

Chatelaine with Watch, Key, and Antique Pendant, circa 1750

Equipages and watches in the first half of the 18th century were incredibly ornate like their 17th century ancestors. This particular equipage includes a unique accessory: a Renaissance pendant from the 1580s that was already over 150 years old when this equipage was constructed!

Chatelaine with étuis (small containers), circa 1755

The small rectangle container from the left dates to about 1730 and was used for snuff which both ladies and gentlemen indulged in.

Chatelaine with watch and charms, circa 1760-70

High-fashion equipages like this functioned as a charm bracelet of sorts for ladies of the court. They were almost completely decorative in nature and might not even have a working watch.

Chatelaine, circa 1775

This equipage has the classic watch-key-seal combination dressed up with gold and a plethora of gemstones!

(IMAGE COPYRIGHTED. PLEASE CLICK HERE TO VIEW IT ON THE ORIGINAL MUSEUM SITE)

Wedgewood Chatelaine, circa 1790

“Suspended from chains attached to the hook are three trinkets: an undecorated carnelian fob; a v-shaped container, possibly for snuff; and a swivel mirror in a case with an engraved hammer and anvil, symbols of force and labor. The missing pendant was in all likelihood the watch key.“

The museum lists this as a gentleman’s chatelaine, but it was probably for a lady since the watch is suspended at the end of the chain.

During the 1780s, it became fashionable for women to wear long watch chains similar to men’s chains. Pairs of watch chains like these were worn with the wildly popular zone front gown or riding habits inspired by the swooped-back cut of a man’s coat and waistcoat. Even though they look very similar to men’s watch chains at the time, they probably clipped or pinned to the petticoat like chatelaines. An article from the Museum of London speculates that ladies may have tucked the watch into their waistband, unless women began including fob pockets in their waistbands or bodices (I haven’t found any evidence of such practice, but if anyone else has, please link to it in the comments below). In all likelihood, the chains were meant to be a display of cutting-edge fashion prowess and wealth rather than functional watch chains:

“Queen Marie Antoinette of France and two of her Children Walking in The Park of Trianon” by Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller, circa 1785

Notice how her watch chains are full of charms, but not necessarily functional watch accessories. The ever-fabulous Aristocat made her own versions, this time including a watch, which you can see here.

Fashion Plate, circa 1787

Wealthy women of the 1780s were said to indulge in wearing two watches at once, a trend borrowed from (and subsequently abandoned by) gentlemen’s fashion. Many fashion plates of this trend show two chains of the same length, but with different configurations. Others, like this one, are perfectly matched and are only loosely “fob-like.”

Fashion Plate, Mid 18th Century

Not all watches at the time were were real. Just as precious jewels were imitated, so were expensive watches! You could buy a case with a painted on dial if you wanted the look without the expense.

By the time the 1790s rolled around, the style of dress had completely changed. The heavily ornate gold equipages were replaced with longer watch chains for both sexes, though ladies’ watches generally remained daintier.

“The Five Positions of Dancing” Illustration, circa 1811

A charming print not just as a dancing reference, but also for all the wonderful watch chains!

Detail of the “Portrait of Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis” by Merry-Joseph Blondel

His dress places this portrait close to his death in 1808. The thick, high cravat style (one of the signature marks of a dandy) was in vogue from about 1800-20, and large, showy watch accessories were favorite pieces of jewelry.

Men’s watch chains/fobs remained in fashion well into the 20th century, and ladies’ chatelaines remained popular through the 19th century until they were replaced with the lady’s handbag by the 1920s. However, wearing watches on a chain never left. Watch necklaces can still be found and were very popular during the mid-20th century, and continue to be worn today. Instead of watches, the smart phone has become the must-have accessory of the 2010s. Much like an equipage or watch string of old, they hold all of our tools in one place for us, complete with fancy cases, accessories, and charms.

For More Information on Georgian Watches, Accessories, and Fobs

On Wearing Two Watches by the Museum of London – Explores the late 18th century trend for wearing two watches at once by both men and women.

Equipages, Chatelaines, and Macaronis by the Museum of London – Explores ways ladies in the 1780s might have worn the double watch chains.

A Watch Fob for My Regency Gentleman by Romantic History – How to make a regency-style watch fob/chain.

My Mr. Knightly: Making Breeches by Tea in a Teacup – How to make historically appropriate breeches with Simplicity 4923 (including fob pocket) and a wonderful set of research links are included.

Cogs and Pieces: Antique Pocket Watches – An online collection of antique time pieces from the 18th century onward and all for sale.

How the Watch was Worn by Genevieve Cummins – A rather spendy book, but a thorough one! I don’t have the privilege of owning a copy, but it is considered the premiere guide to historical watch wearing.